Indexing & Abstracting

Full Text

Review ArticleDOI Number : 10.36811/ojgor.2019.110004Article Views : 2577Article Downloads : 36

Niche After Cesarean Section

Mohamed Nabih EL-Gharib

Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt

*Corresponding author: Mohamed Nabih EL-Gharib, MB, BCH (Hon); DGO; DS; MD (OB/GYN), Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt, Tel: +201117040040; Email: mohgharib2@hotmail.com

Article Information

Aritcle Type: Review Article

Citation: Mohamed Nabih EL-Gharib. 2019. Niche After Cesarean Section. O J Gyencol Obset Res. 1: 19-25.

Copyright: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Copyright © 2019; Mohamed Nabih EL-Gharib

Publication history:

Received date: 16 March, 2019Accepted date: 26 March, 2019

Published date: 28 March, 2019

Abstract

A uterine niche, also calld cesarean scar defect, or cesarean scar dehiscence, uterine diverticulum, uterine sacculation or isthmocele. It is a man made pouchlike defect of the anterior uterine isthmus occurs at the site of a prior cesarean section. Its occurrence has been increased in the last years secondary to the increased incidence of cesarean section. Many patients with isthmocele are asymptomatic. The most frequent complaint relates to intermittent postmenstrual bleeding as the isthmocele functions as a reservoir collecting blood during menstruation, with irregular menses that can run for 2 to 12 days. Various sources have described isthmocele as a case of infertility, pain and dysmenorrhea. An isthmocele is typically diagnosed on transvaginal sonography, hysterosalpinography and hysteroscopy. Magnetic resonance tomography is useful to measure the thickness of the lower uterine segment, the profundity of the isthmocele. The treatment of isthmocele includes laparotomy, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, vaginal repair, and several combined techniques with no statistically superior outcome noted in the literature. In that respect is no gold standard treatment for isthmocele.

Keywords: Niche; Isthmocele; Uterine sacculations; Cesarean section complications

Introduction

An isthmocele, also called a niche, cesarean scar defect, cesarean scar dehiscence, uterine diverticulum, pouch, or sacculation. It is a pouchlike defect of the anterior uterine isthmus at the site of a prior cesarean section [1], which was ?rst described by Morris in 1995 [2]. An isthmocele is a man-made lake-like pouch defect in the anterior wall of the uterine isthmus located at the site of the previous cesarean scar. Therefore, the cesarean-induced isthmocele may lead to the occurrence of gynecologic symptoms such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) secondary to intermittent passage of retained menstrual blood within the cesarean scar defect (CSD), pelvic pain, and sterility [1,3]. The ?rst scar defect ever reported was in 1975 when Stewart, et al who noted that preoperative historiography or pelvic arteriography might help with diagnosis and that the uterus could be saved by excision of the lower segment scar [4]. The worldwide prevalence of isthmoceles out of all cesarean sections ranges from 19% to 84% [5], but this may be underrated because of asymptomatic patients and a lack of clinician awareness. Sonohysterography (SHG) identi?ed a higher number of patients with isthmoceles (56%-78%) than transvaginal ultrasound (24%-69%) as noted by van der Voet et al [6].

There is an increasing tendency for cesarean delivery worldwide. Although several obstetric complications such as placenta accreta, scar dehiscence, and ectopic scar pregnancy due to inappropriately heal uterine lower segment incision have been reported, gynecologic sequela are increasingly reported in the last decade [7] It has been 30 years since the World Health Organization issued a statement warning about the high rate of cesarean sections and recommending a maximum 15% rate of surgical intervention [8]. Despite this, the United States reported an increase of 50% in cesarean sections from 1996 to 2007; [9] and other nations such as Brazil reported an overall cesarean section rate of 45% and a private practice rate of 81% [10].

In Egypt, the past decade has seen a precipitous growth in the prevalence of CS with the most recent Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) documenting a CS rate of 52%, which suggests that cesarean delivery might be overused or used for inappropriate indications [11]. In the UK the figure stands at barely over 26%, but in some countries more than half of births involve the procedure: in the Dominican Republic over 58% of babies are presented this way, while in Egypt the figure is 63% when looking just at births in institutional contexts [12]. The relationship between different types of uterine closure and the prevalence of cesarean scar defects is unclear. Although the risk for a uterine scar defect was shown to increase in single-layer myometrial closure compared with double-layer closure. Although the rate of large scar defects was doubled in singlelayer closure, this difference was not statistically signi?cant. The lack of association between the closing technique and scar defect size could be caused by type II statistical error [13].

Symptoms

Many patients with isthmoceles are asymptomatic, and patients might consult with different physicians before the right diagnosis is found. The most frequent complaint relates to intermittent postmenstrual bleeding. The isthmocele functions as a reservoir collecting blood during menstruation, with irregular menses that can run for 2 to 12 days [14]. Various sources have described isthmoceles as a case of infertility, stating de?cient sperm motility and implantation [15,16]. Pain and dysmenorrhea are general symptoms common to numerous gynecologic causes. The relationship between isthmoceles and pain is not clear, but could be linked to abnormal myocontraction caused by physiological irregularities and continuous efforts of the uterus to evacuate the contents of the isthmocele. Wang et al found a signi?cant relationship among dysmenorrhea, the breadth of the defect, and abnormal bleeding [17].

Diagnosis

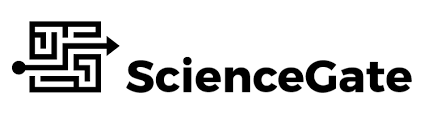

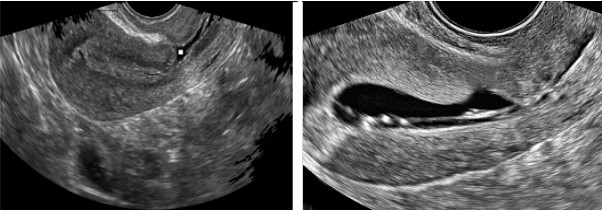

An isthmocele is typically diagnosed on transvaginal sonography and appears as a wedge-shaped anechoic area with a depth of at least 1 mm and an indentation of the myometrium of at least 2 mm in the uterine isthmus at the cesarean section scar site [16], Ultrasound is used to measure the depth and size (longitudinal) of the dehiscent scar and the thickness of the residual myometrium covering the dehiscence (Figure 1). The diagnosis of a cesarean scar defect can also be performed by direct visualization with hysteroscopy. On hysteroscopy, the defect is observed as a bulge on the anterior wall of the uterine isthmus (Figure 2). Hysterosalipigography can also help in the diagnosis of uterine niche as depicted in figure 3. Magnetic resonance tomography is useful to measure the thickness of the lower uterine segment, the profundity of the isthmocele, and the substance of the endometrial and niche cavity.

Figure 1: Ultrasonographic images of the uterus. The anechoic area in the anterior uterine wall was the uterine defect surrounded by thin residual myometrium.

Figure 2: The hysteroscopic view of the niche.

Figure 3: Anteroposterior and lateral view a of hysteroslapingram of the uterus showing the uterine scar diverticulum.

Treatments

If indicted, repair of the niche is made from various route: laparotomy, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, vaginal repair, and several combined techniques with no statistically superior outcome noted in the literature. In that respect is no gold standard treatment for isthmocele.

Medical treatment: Medical treatment is the best for women with isthmocele who do not desire to get pregnant seems to be oral contraception. Zhang et al. [18], have published a survey on the role of oral contraceptives with estrogen and progesterone in 18 patients and have found it to be effective regarding the duration of flow (reducing from 10 days to 5 days). Other authors [19] have also described oral contraceptives to be efficacious in reducing bleeding disorders. Florio et al. [20], have described less bleeding and less pain after the use of oral contraceptives or hysteroscopic resection with better results in women undergoing hysteroscopic correction compared with oral contraceptives. The usage of an intrauterine device with levonorgestrel has not shown a bene?t in these women [21].

Vaginal Surgery: Transvaginal repair surgery was performed under general anesthesia. Patients were placed in a dorsal lithotomy position and the bladder emptied before the surgery. For hydrodissection and hemostasis, adrenaline (1:200 000) was injected into the vesicocervical space. A transverse incision was made at the anterior cervicovaginal junction. The bladder was then dissected away from the uterus and retracted upward by the anterior drawing hook. The location of the uterine defect was determined under the guidance of a probe in the uterus. A transverse incision was then made at the most prominent area of the defect, and the defect was removed. Subsequently, an interrupted horizontal transverse ?gure-8-pattern suture was used for the ?rst layer of closure with 0 absorbable sutures. The mattress suture was used in the second layer, and the vaginal epithelium was then continuously sutured using 0 absorbable sutures. Finally, the vagina was packed with 2 pieces of iodoform gauze, which were removed after 24 to 48 hours [18]. Zhang reported no complications (14 patients). This technique requires surgical expertise to avoid damaging the surrounding organs. It also necessitates that the isthmocele is not too high or vaginal correction would be dif?cult [21]. Outcomes show that menstruation duration diminishes after treatment and myometrial thickness increases. Most patients experience symptom relief [18]. Zhang et al and Xie et al have noted a resulting 22% pregnancy rate [21,22].

Laparoscopic resection of the niche: Excision of uterine sacculation (niche) with uterine reconstruction is a conservative surgical laparoscopic technique that should be studied by a selected group of patients in whom fertility sparing is desired.The laparoscopic localization of the niche is generally guided by translucency of a 5 mm hysteroscope or by a Hegar probe. First the bladder is dissected from the uterus and the niche is opened and excised. Next, all ?brotic tissue in the uterine scar is excised in order to Enable proper wound healing. Then, the myometrium is sutured in one or two layers. The use of an adhesion barrier can be applied in order to reduce reformation of adhesions. The effect on the niche is evaluated after surgery by hysteroscopy. A urinary Foley catheter is generally removed after approximately 6-12 hours [23].

Hysteroscopy: Most authors treated symptomatic cesarean scar defects with hysteroscopy. Niche resection by hysteroscope is the least invasive of these techniques, but requires a sufficient thick residual myometrium between the niche and the bladder is suf?ciently thick to prevent bladder injury.The cut-off value of the residual myometrium in various studies varies between 2.5 and 4.0 mm, as measured using sonohysterography (Figure 4). Cervical dilation was performed using Hegar dilators(9). A hysteroscopic niche resection can be performed in different ways; the distal rim can be resected to facilitate menstrual outflow (Figure 5), both distal and proximal part of the niche can be resected and it can be combined with coagulation of the vessels in the niche or the entire niche surface to prevent bleeding from the fragile vessels. The entire ?brotic part of the scar should be removed and the muscular part has been reached. The niche surface will be superficially coagulated [24,25].

Postoperative Advice

It is advisable for a women to use contraception during the ?rst 6 months. After six months women are allowed to conceive. There is no solid evidence of the minimal required period for healing of the uterine wound to host a subsequent pregnancy [26].

References

- Gubbini G, Casadio P, Marra E. 2018. Resectoscopic correction of the “isthmocele” in women with postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding and secondary infertility. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 15: 172-175. [Ref.]

- Morris H. 1995. Surgical pathology of the lower uterine segment caesarean section scar: is the scar a source of clinical symptoms? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 14: 16-20. [Ref.]

- Wang CB, Chiu WW, Lee CY, et al. 2009. Cesarean scar defect: correlation between cesarean section number, defect size, clinical symptoms uterine position. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 34: 85-89. [Ref.]

- Stewart KS, Evans TW. 1975. Recurrent bleeding from the lower segment scar-a late complication of Caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 82: 682-686. [Ref.]

- Bij de Vaate AJ, van der Voet LF, Naji O, et al. 2014. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 43: 372-382. [Ref.]

- van der Voet LF, Vervoort AJ, Veersema S, et al. 2014. Minimally invasive therapy for gynaecological symptoms related to a niche in the caesarean scar: a systematic review. BJOG. 121: 145-156. [Ref.]

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. 2013. Cesarean scar defects: an unrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 20: 562-572. [Ref.]

- Robson SJ, de Costa CM. 2017. Thirty years of the World Health Organization’s target caesarean section rate: time to move on. Med J Aust. 206: 181-185. [Ref.]

- Barber EL, Lundsberd L, Belanger K, et al. 2011. Contributing indications to the rising cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 118: 29-38. [Ref.]

- Barros AJ, Santos IS, Matijasevich A, et al. 2011. Patterns of deliveries in a Brazilian birth cohort: almost universal cesarean sections for the better off. Rev Saude Publica. 45: 635-643. [Ref.]

- Abdel-Tawab N, Oraby D, Hassanein N, et al. 2018. Caesarean section deliveries in egypt: trends, practices, perceptions and cost.[Ref.]

- Davis N and Long C. 2018. Use of caesarean sections growing at 'alarming' rate. The Guardian, International edition.[Ref.]

- Hayakawa H, Itakura A, Mitsui T, et al. 2006. Methods for myometrium closure and other factors impacting effects on cesarean section scars of the uterine segment detected by the ultrasonography. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 85: 429-434. [Ref.]

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. 2013. Cesarean scar defects: an underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 20: 562-572. [Ref.]

- Gubbini G, Centini G, Nascetti D, et al. 2011. Surgical hysteroscopic treatment of cesarean-induced isthmocele in restoring fertility: prospectistudy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 18: 234-237. [Ref.]

- Tulandi T, Cohen A. 2016. Emerging manifestations of cesarean scar defect in reproductive-aged women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 23: 893-902. [Ref.]

- Wang CB, Chiu WW, Lee CY, et al. 2009. Cesarean scar defect: correlation between Cesarean section number, defect size, clinical symptoms and uterine position. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 34: 85-89. [Ref.]

- Zhang X, Yang M, Wang Q, et al. 2016. Prospective evaluation of ?ve methods used to treat cesarean scar defects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 134: 336-339. [Ref.]

- Tahara M, Shimizu T, Shimoura H. 2006. Preliminary report of treatment with oral contraceptive pills for intermenstrual vaginal bleeding secondary to a cesarean section scar. Fertil Steril. 86: 477-479. [Ref.]

- Florio P, Gubbini G, Marra E, et al. 2011. A retrospective case-control study comparing hysteroscopic resection versus hormonal modulation in treating menstrual disorders due to isthmocele. Gynecol Endocrinol. 27: 434-438. [Ref.]

- Zhang Y. 2016. A comparative study of transvaginal repair and laparoscopic repair in the management of patients with previous cesarean scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 23: 535-541. [Ref.]

- Xie H, Wu Y, Yu F, et al. 2014. A comparison of vaginal surgery and operative hysteroscopy for the treatment of cesarean induced isthmocele: a retrospective review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 77: 78-83. [Ref.]

- Donnez O, Donnez J, Orellana R, et al. 2017. Gynecological and obstetrical outcomes after laparoscopic repair of a cesarean scar defect in a series of 38 women. Fertil Steril. 107: 289. [Ref.]

- van der Voet LF, Vervoort AJ, Veersema S, et al. 2014. Minimally invasive therapy for gynaecological symptoms related to a niche in the caesarean scar: a systematic review. BJOG. 121: 145-156. [Ref.]

- Cohen SB, Mashiach R, Baron A, et al. 2017. Feasibility and ef?cacy of repeated hysteroscopic cesarean niche resection. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 217: 12-17. [Ref.]

- Huirne JAF, Vervoort AJMW, Leeuw RDe, et al. 2017. Technical aspects of the laparoscopic niche resection, a step-by-step. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 219: 106-112. [Ref.]