Indexing & Abstracting

Full Text

Research ArticleDOI Number : 10.36811/ijrmsh.2019.110002Article Views : 1502Article Downloads : 26

Is induced abortion becoming a family planning method in Ghana?: A situational analysis of induce abortion and contraception uptake in two urban cities of Ghana

Fred Yao Gbagbo1*and Josephine Akosua Gbagbo2

1University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

2Ngleshie Amanfro Senior High School, Ghana

*Corresponding author: Fred Yao Gbagbo, University of Education, Winneba. P. O. Box 25, Winneba. Ghana, Tel: +233(0)243335708; Email: gbagbofredyao2002@yahoo.co.uk

Article Information

Aritcle Type: Research Article

Citation: Fred Yao Gbagbo, Josephine Akosua Gbagbo. 2019. Is induced abortion becoming a family planning method in Ghana?: A situational analysis of induce abortion and contraception uptake in two urban cities of Ghana. Int J Reprod Med Sex Health. 1: 08-23.

Copyright: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Copyright © 2019; Fred Yao Gbagbo

Publication history:

Received date: 20 March, 2019Accepted date: 28 March, 2019

Published date: 29 March, 2019

Abstract

Background: Following amendment of Ghanaian abortion law in 1985, abortion services became more available as permitted by law. Services data however remain scares due to provider and facility stigmatization.

Objective: To explore the use of abortion as a family planning option using provider reports, trends of contraception and induced abortion service uptake in facilities within two urban cities in Ghana.

Methods: Cross-sectional, descriptive design, using facility data from 50 private (42) and Non-Governmental Organizations (8). Ten in-depth interviews were also held with midwife providers (6) and medical officers (4) between January 2010 and December 2017 in Accra and Kumasi Metropolises.

Results: Facility patronage of abortion services in Accra and Kumasi Metropolises increase steadily each year with contraception uptake. Abortion services in NGO facilities were however reported as target driven and providers’ performances/bonuses were tied to meeting set targets thereby encouraging abortion on demand. Whereas NGO facilities provide both abortion and full contraception method mix, majority (38 out of 42) of private facilities provide only abortion services. Those providing contraception focus mainly on short term methods (pills and injections) due to lack of interest and/or trained providers. There are more midwife lead abortion providing facilities in Accra (40) than in Kumasi (10). Where midwives provided abortion services, contraceptives were readily available and clients encouraged to take a method following abortion. This practice was very common in NGO facilities as post abortion contraception was reported to be a mandatory package.

Conclusions: The Ghanaian abortion law allows conditional abortion and not on demand. However, increasing numbers of abortions in the study area coupled with reported target setting for abortion services suggest abortion on demand and its being used as a family planning option. A nationwide facility based assessment of abortion and contraception service delivery is recommended to inform policy.

Keywords: Contraception; Demand; Family planning; Induced abortion; Urban cities, Ghana

Introduction

Following the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) recognition that appropriate family planning methods for couples and individuals vary by various factors including their age, parity, and family size-preference, countries have pledged commitments to ensure that women and men have information and access to the widest possible range of safe and effective family planning methods in order to enable citizens to exercise free and informed contraceptive choices [1]. The reality in most countries, however, is far different since most countries offer only a limited choice of contraceptive methods, and couples cannot easily make a choice resulting in unmet need for contraceptives hence induced abortions [2]. Globally, unmet need for contraception is a major cause of unsafe abortion [3]. The situation in Ghana is not too different from what pertains in other countries globally although records of contraception and unsafe abortion in Ghana are better than in neighboring African countries [4-6]. The Unmet need for contraception (% of married women ages 15-49) in Ghana was 30.6% as of 2016. Over the past 27 years this indicator reached a maximum value of 37.20 in 2013 and a minimum value of 26.40 in 2011, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators. Although data on induced abortion in Ghana is limited to institutional records hence inadequate for optimal interventions, the Government of Ghana has taken important steps to mitigate the impact of unsafe abortion [7].

This study aims to review and present findings on induced abortion and contraception uptake in the two most populous urban cities (Accra and Kumasi) of Ghana. Findings of this review can be used to monitor and evaluate the success of family planning and safe abortion programs over a period of time for further policy and program decision making in Ghana.

Methods

Study design

The study design was cross-sectional, multistage and descriptive in nature. The study used secondary data from institutional records and narrations from abortion providers in perceived most popular health facilities run by private and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) in Accra and Kumasi. Ten in-depth interviews were also held with midwife providers (6) and medical officers (4) in Accra and Kumasi between January 2010 and December 2017.

Study population

The study population comprised all females who received contraceptive and induced abortion services from health facilities in Accra and Kumasi metropolises. A total of fifty (50) facilities comprising 8 NGO owned and 42 private for profit owned facilities with good management information systems for data capturing were purposively sampled for the study. Identification of the study facilities for sampling was based on key informants’ perceived popularity of these facilities for providing Family Planning and induced abortion service in the study area.

Study setting

The study was conducted in Accra and Kumasi metropolises due to the cosmopolitan nature of the two cities and widely availability of abortion services. Accra is the capital and largest city of Ghana, covering an area of 225.67 km2 (87.13 sq mi) with an estimated urban population of 2.27 million as of 2012. It is organized into 10 local government districts -9 municipal districts and the Accra Metropolitan District, which is the only district within the capital to be granted city status. "Accra" usually refers to the Accra Metropolitan Area, which serves as the capital of Ghana, while the district within the jurisdiction of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly is distinguished from the rest of the capital as the "City of Accra". In common usage, however, the terms "Accra" and "City of Accra" are used interchangeably. The central business district of Accra contains the city's main banks and department stores, as well as an area known as the Ministries, where Ghana's government administration is concentrated. Economic activities in Accra include the financial and commercial sectors, fishing and the manufacture of processed food, lumber, plywood, textiles, clothing and chemicals. Tourism is becoming a thriving source of business for those in arts and crafts, historical sites and local travel and tour agents. The Oxford Street in the district of Osu has grown to become the hub of business and night life in Accra [8].

Kumasi (historicallyspelt Comassie or Coomassie and usually spelt Kumase in Twi) is a city in Ashanti Region, and is among the largest metropolitan areas in Ghana with a total population of 2,069,350 and density 8,100/km2(21,000/sq mi). Kumasi is near Lake Bosomtwe, in a rain forest region, and is the commercial, industrial and cultural capital of Asanteman. Kumasi is approximately 500 kilometres (300 mi) north of the Equator and 200 kilometres (100 mi) north of the Gulf of Guinea. Kumasi is alternatively known as "The Garden City" because of its many beautiful species of flowers and plants. It is also called Oseikrom (Osei Tutu's town). Kumasi is described as Ghana’s second city because almost every diplomatic and evolving uplift to a city that makes it number one is situated/ created in the country's capital (This is problem some citizens complain about) but Kumasi has every trait and effort to be Ghana's first city. The Central Business District of Kumasi includes areas like Adum, Bantama and Bompata (popularly called Roman Hill) is concentrated with lots of banks, department stalls, hotels like Golden Tulip Hotel, Golden Bean Hotel among other luxury hotels. Economic activities in Kumasi include financial and commercial sectors, pottery, clothing and textile. There is a huge timber processing community in Kumasi which serves the needs of people in Ghana. The Bantama High Street and the Prempeh II Street in Bantama and Adum respectively have the reputation of being the hub of business and night life in Kumasi [9].

Ethical considerations

Permission was obtained from respondents and the participating facilities involved in the study. In this regard, data was collected and managed in a way that did not compromise the privacy and confidentiality of clients, participating facilities and respondents involved in the study.

Data collection procedure

Data collection for the study was in two parts. The first part was in six stages. The first stage was identification of private and NGO health facilities providing abortion and contraception services in Accra and Kumasi using taxi drivers as key informants. The second stage was to map the locations of the identified health facilities and cluster them by proximity. The third stage was to use ten trained research assistants as mystery clients (five each from Accra and Kumasi) to verify and authenticate if the identified facilities actually provide contraception and abortion services for sampling. The fourth stage was a follow-up visit to the identified facilities to seek permission for data collection. The fifth stage was data collection using field officers. The sixth stage was independent data validation by confirmation from the facilities. The contraception and induced abortion figures were extracted from various sources. In facilities that had good electronic client information data base the service numbers were generated from the system directly. For those that did not have a robust Information Management Systems, data was manually collected from the cash book records and service reports. The data collection did not involve clients’ folders to ensure optimal privacy and confidentiality of identity. The second part of data collection was in-depth interviews with service providers in the facilities that recorded hundred and above induced abortion services to provide qualitative information on the reasons(s) behind the figures. Ten in-depth interviews were held with six midwife providers and four medical officers in Accra and Kumasi respectively. The total duration for data collection was six months. The service delivery data used was between January 2010 and December 2017. The in-depth interviews were conducted in December 2017.

Results

Table 1: Presents some background characteristics of the facilities sampled for the study. There was more private owned abortion delivery facility than those of the NGOs. Also, the number of perceived popular abortion clinics in Accra were more than those observed in Kumasi metropolis.

Three top-level pole dancers volunteered to participate in this study, carried out in September 2017. Some relevant biometrics are reported in table 1.

| Table 1: Background Characteristics of participating facilities. | ||||||

| Facility | Classification | Ownership | Location | Availability of Abortion/FP services | Type of FP services available | Type of Abortion services available |

| 1. | SRH Centre | NGO | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 2. | SRH Centre | NGO | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 3. | SRH Centre | NGO | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 4. | SRH Centre | NGO | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 5. | SRH Centre | NGO | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 6. | SRH Centre | NGO | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 7. | Hospital | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 8. | Hospital | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 9. | Hospital | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LAPM | MA & SA |

| 10. | Hospital | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 11. | Hospital | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 12. | Hospital | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 13. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 14. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 15. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 16. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 17. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 18. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 19. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 20. | Hospital | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 21. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 22. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 23. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 24. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 25. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 26. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 27. | Clinic | Private | Accra | Abortion only | Nill | SA only |

| 28. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 29. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 30. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 31. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 32. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 33. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 34. | Clinic | Private | Kumasi | Abortion only | Nill | MA & SA |

| 35. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA only |

| 36. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 37. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 38. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 39. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 40. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA only |

| 41. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA only |

| 42. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA only |

| 43. | Maternity Home | Private | Accra | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA only |

| 44. | Maternity Home | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA & SA |

| 45. | Maternity Home | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM only | MA & SA |

| 46. | Maternity Home | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 47. | Maternity Home | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| 48. | Maternity Home | Private | Kumasi | Abortion &FP services | STM & LARC | MA & SA |

| Source: Field data January 2010-December 2017. [FP=Family planning; MA=Medication Abortion; SA=Surgical Abortion; STM=Short Term Methods; LARC= Long Acting &Reversible Contraception Methods; SRH=Sexual and Reproductive Health). | ||||||

| Table 2: Consolidated Contraception & Induced Abortion figures (January2010-December 2017). | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of services | |||||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | |

| Injectables - 1 month | 1,918 | 6,682 | 12,480 | 14,781 | 15,401 | 17,694 | 16,290 | 15,023 | 100,269 |

| Injectables - 3 month | 19,573 | 29,383 | 31,511 | 36,850 | 45,538 | 48,511 | 53,906 | 43,828 | 309,100 |

| Oral Pills | 14,647 | 24,507 | 29,011 | 40,874 | 58,953 | 10,347 | 15,878 | 5,571 | 199,788 |

| Emergency Contraception | 7,806 | 10,002 | 16,205 | 20,447 | 26,199 | 60,483 | 16,177 | 785 | 158,104 |

| Total STMS | 767,261 | ||||||||

| IUDs | 2,469 | 2,543 | 1,809 | 6,468 | 5,943 | 7,159 | 7,715 | 11,888 | 45,994 |

| Implants | 3,117 | 14,433 | 23,017 | 40,657 | 39,868 | 48,726 | 54,325 | 68,314 | 292,457 |

| Tubal Ligations | 312 | 842 | 1,388 | 1,578 | 1,913 | 1,483 | 1,373 | 1,896 | 10,785 |

| Total LAPMs | 5,907 | 17,823 | 26,232 | 48,742 | 47,764 | 57,418 | 63,474 | 82,154 | 349,236 |

| Surgical | 10,007 | 17,183 | 16,817 | 18,238 | 23,804 | 23,654 | 22,774 | 23,852 | 156,329 |

| Medical | 2,177 | 3,576 | 7,450 | 11,096 | 13,198 | 19,297 | 18,282 | 9,456 | 84,532 |

| Total Induced Abortion | 12,184 | 20,759 | 24,267 | 29,334 | 37,002 | 42,951 | 41,056 | 33,308 | 240,861 |

| Source: Field data January2010-December 2017. | |||||||||

Some service providers explained the rationale behind focusing mainly on abortion and making efforts towards increasing abortion figures during the in-depth interviews as follows: ‘We are given annual abortion targets to achieve each year. Our key performances indicators and bonuses are therefore tied to the number of abortions we provide’ (Midwife, NGO Owned facility).

Another provider indicated that: ‘If I counsel women seeking abortion services to choose other options, how will I meet my targets and make more money since the main source of income in this facility is through abortion’ (Medical officer, Private facility).

Another abortion provider revealed that ‘many young girls visit this facility more than three times in a year to terminate an unplanned pregnancy. Some even request to abort big pregnancies (>18 weeks) whom I always refer’ to other private facilities because I don’t terminate big pregnancies’ (Midwife, NGO Owned facility).

In the case of increasing family planning service, there appear to be some coercion of clients as provision of abortion services are tied to acceptance to take a family planning method prior to an abortion. A service provider explained as follows: ‘I am always angry with young girls who come to my clinic for abortion so I force them to take a family planning method before I do the abortion, because I don’t want them to come back for another abortion’ (Midwife, Private facility).

Another service provider reported that: ‘We have monthly targets set for Long acting and reversible contraception uptake following an abortion and so we do everything possible in our facility to ensure that women we provide abortion services leave with a method so as to meet our monthly targets’ (Midwife, NGO Owned facility).

Another provider indicated that: ‘In our facility, family planning services are not available because it’s not really our focus. We are specialized in providing abortion services which we do well. Clients requiring family planning services could visit other facilities that provide such services’ (Medical officer, Private facility).

Table 3 and 4 presents facility specific contraception and induced abortion figures for January 2010 to December 2017. The NGO owned facilities provided higher numbers of contraception and abortion services than the private facilities. In both the NGO and private owned facilities, surgical abortion services also outnumber the medication abortion services. Both facilities provided more short term family planning services and more surgical abortion services than other services. The cadre of family planning service providers in both the private and NGO facilities influenced the availability and options of family planning services offered in both facilities. A respondent explained that: ‘As an NGO, we belief in task sharing reproductive health services with midlevel providers, provided they are well trained and certified by national laws’ (Midwife, NGO Facility).

Other respondents explained that: ‘There are more midwives in Ghana than medical officers. Besides family planning services are usually provided by midwives and Ghana also allows midwives to provide abortion services up to 9weeks if trained and certified so these days we are providing abortion services in hospitals hence the increase in the numbers’ (Midwife, private Facility). The availability of trained and competent abortion and contraceptive providers in facilities also determines services delivery hence the numbers. In facilities where a trained provider is not available service delivery is limited to the capability of the providers. Some providers indicate that: ‘For me I’m only trained on short term methods and so allowed to give only injectables and pills’. (Midwife, in private owned facility).

| Table 3: Contraception and induced abortion service numbers from NGO facilities. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of services | |||||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | |

| Injectables - 1 month | 1,795 | 5,254 | 9,957 | 9,959 | 7,859 | 5,754 | 4,041 | 4,247 | 48,866 |

| Injectables - 3 month | 12,931 | 17,218 | 17,640 | 20,621 | 20,983 | 17,109 | 17,084 | 16,616 | 140,202 |

| Oral Pills | 2,842 | 4,645 | 6,009 | 2,410 | 2,168 | 2,349 | 2,227 | 2,541 | 25,191 |

| Emergency Contraception | 173 | 185 | 174 | 183 | 35 | 3 | 27 | 11 | 791 |

| Total STMs | 215,050 | ||||||||

| IUDs | 1,863 | 1,158 | 1,163 | 1,445 | 1,926 | 2,261 | 2,643 | 2,689 | 15,148 |

| Implants | 1,758 | 1,477 | 2,159 | 3,994 | 3,894 | 4,190 | 5,557 | 5,135 | 28,164 |

| Tubal Ligations | 0 | 2 | 8 | 22 | 41 | 46 | 85 | 171 | 375 |

| Total LAPMs | 3,625 | 2,639 | 3,334 | 5,469 | 5,870 | 6,507 | 8,315 | 8,021 | 43,687 |

| Surgical | 4,773 | 5,528 | 5,192 | 4,667 | 4,635 | 4,892 | 5,106 | 7,201 | 41,994 |

| Medical | 1,875 | 2,491 | 5,439 | 5,832 | 5,514 | 5,513 | 6,690 | 6,461 | 39,815 |

| Total Induced Abortion | 6,648 | 8,019 | 10,631 | 10,499 | 10,149 | 10,405 | 11,796 | 13,662 | 81,809 |

| Field data January 2010 to December 2017. | |||||||||

The cadre of family planning service providers in both the private and NGO facilities influenced the availability and options of family planning services offered in both facilities. A respondent explained that: ‘As an NGO, we belief in task sharing reproductive health services with midlevel providers, provided they are well trained and certified by national laws’ (Midwife, NGO Facility). Other respondents explained that: ‘There are more midwives in Ghana than medical officers. Besides family planning services are usually provided by midwives and Ghana also allows midwives to provide abortion services up to 9weeks if trained and certified so these days we are providing abortion services in hospitals hence the increase in the numbers’ (Midwife, private Facility. The availability of trained and competent abortion and contraceptive providers in facilities also determines services delivery hence the numbers. In facilities where a trained provider is not available service delivery is limited to the capability of the providers. Some providers indicate that: ‘For me I’m only trained on short term methods and so allowed to give only injectables and pills’. (Midwife, in private owned facility).

| Table 4: Contraception and induced abortion service numbers from private facilities. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of services | |||||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | |

| Injectables-1 month | 123 | 1,428 | 2,523 | 4,822 | 7,542 | 11,940 | 12,249 | 10,776 | 51,403 |

| Injectables-3 month | 6,642 | 12,165 | 13,871 | 16,229 | 24,555 | 31,402 | 36,822 | 27,212 | 168,898 |

| Oral Pills | 11,805 | 19,862 | 23,002 | 38,464 | 56,785 | 7,998 | 13,651 | 3,030 | 174,597 |

| Emergency Contraception | 7,633 | 9,817 | 16,031 | 20,264 | 26,164 | 60,480 | 16,150 | 774 | 157,313 |

| Total STMs | 552,211 | ||||||||

| IUDs | 605 | 821 | 288 | 3,031 | 2,312 | 2,576 | 2,551 | 4,999 | 17,183 |

| Implants | 1,359 | 2,532 | 2,953 | 8,216 | 8,538 | 9,526 | 13,229 | 25,763 | 72,116 |

| Tubal Ligations | - | 12 | - | 16 | 114 | 17 | 4 | 9 | 172 |

| Total LAPMs | 1,964 | 3,365 | 3,241 | 11,263 | 10,964 | 12,119 | 15,784 | 30,771 | 89,471 |

| Surgical | 5,234 | 11,655 | 11,625 | 13,571 | 19,169 | 18,762 | 17,668 | 16,651 | 114,335 |

| Medical | 302 | 1,085 | 2,011 | 5,264 | 7,684 | 13,784 | 11,592 | 2,995 | 44,717 |

| Total Induced Abortion | 5,536 | 12,740 | 13,636 | 18,835 | 26,853 | 32,546 | 29,260 | 19,646 | 159,052 |

| Source: Field data January 2010 to December 2017. | |||||||||

Another provider indicated that: ‘We don’t have anybody trained on tubal ligations in this facility. Hence clients who opt for this service after an abortion are either referred to other facilities or convinced to take other methods that we have the skills and supplies to provide. Occasionally, we invite the surgeons to provide tubal ligations but the cost very expensive for some clients since they have to pay as laparotomy done in theater’ (Medical officer, Private facility).

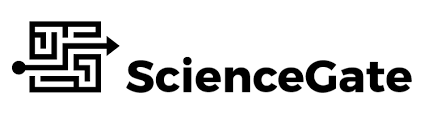

Consolidated trends in contraception and induced abortions 2010-2017: The consolidated contraception and induced abortion statistics in the private and NGO facilities shows increasing trends of service numbers within the seven year period of review. For instance in figure 1, there was a steady increase in all the STM contraceptive uptake between 2010 and 2014 with a high spike in uptake of emergency contraceptives in 2015.

Figure 1: Consolidated contraceptive uptake trends in private and NGO facilities: 2010-2017.

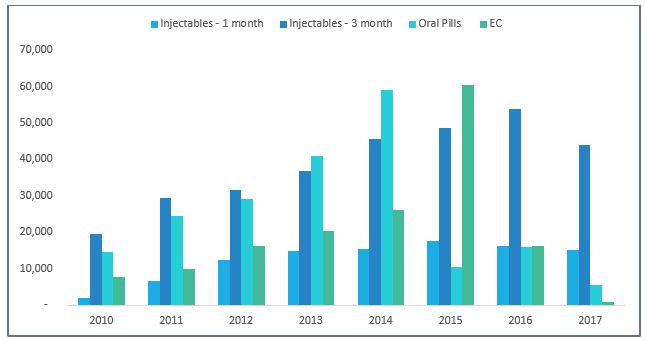

Uptake of Implants have been consistently high in all facilities between 2010 and 2017. Intrauterine Contraceptive Devices (IUDs) also showed a similar trend except a slight deviation from the trend in 2013 where IUD uptake showed a marginal increase figure 2.

Figure 2: Consolidated Long Acting and Reversible Contraception (LARC) trends in private and NGO facilities: 2010-2017.

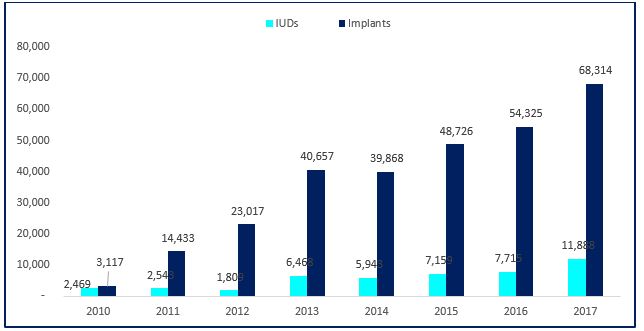

The patronage of induced abortion services (both surgical and medical) in the two cities have also increased steadily with surgical abortions topping in all the facilities studied (figure 3).

Figure 3: Consolidated trends of induced abortion uptake in the private and NGO facilities: 2010-2017.

Discussions

Ghana was among the first sub-Saharan African countries to adopt a national population policy, in 1969 [10]. Despite the high importance placed on sexual and reproductive health including family planning activities by national policies, strategies, and plan of actions, family planning programs remain a challenge, hence affecting progress towards the set sexual and reproductive health targets. Anecdotal evidences suggests that, the range of available sexual and reproductive health services in health facilities have insignificant relations with clients centered care, leading to the suspicion that some of the services are placed according to patterns of demand, provider financial gains and not tailored to enable clients to make informed decisions to address their sexual and reproductive health needs.

The facilities selected for this study were in three (3) categories of varying characteristics with respect to services classification, ownership and service(s) provided. It was noted that whereas some facilities provide both abortion and family planning services, others in the study area provided only induced abortion services and not contraception services. There appear to be more induced abortion service providers in Accra than Kumasi metropolis. This is due to the varying nature of contraception and induced abortion services noted in the facilities. The study extracted and consolidated contraception and induced abortion figures covering January 2010-Decemebr 2017 from the NGO facilities and private facilities. A total of 1,116,775 Family planning services (767,261 Short Term Methods and 349,514 Long Acting/Permanent Methods) and 240,861 Induced Abortions (156,329 Surgical and 84,532 Medical were recorded. There appeared to have been more Short-Term Methods of family planning services than Long Acting/Permanent Methods. Additionally, surgical abortion numbers were 71,797 more than induced abortions using medical options.

Although various cadre of providers were observed, midwives were the majority of induced abortion and contraception services providers in health facilities within Accra than in Kumasi. In Facilities where midwives provided abortion services, clients were encouraged to take a contraceptive method. This practice was very common in NGO facilities.

The observation that some facilities set targets for services questions the voluntary nature of service uptake. Induced abortion and/or contraception services are technically/ethically expected to be voluntary and preceded by options counselling to enable clients make informed decisions and choices. Target setting as a key performance indicator for service providers particularly for abortion services is an indication of service providers and facilities encouraging abortion on demand through possible coercion of clients to meet their set targets. Good clinical practices have shown that, where women are given good counselling prior to clinical services, rates of regrets are minimal and client satisfaction is assured [11,12].

The observation that NGO owned facilities provided higher numbers of contraception and abortion services than the private facilities have implications for quality or aggressive marketing of services. In Ghana although abortion is legally permissible by law, advertising clinical facilities providing abortion services is socially stigmatized [13]. One will therefore expect that abortion services in particular are not aggressively marketed but designed to meet the unique needs of clients as permitted by law. Increasing numbers of abortion services in Ghana annually undermines public health efforts in promoting contraceptive security to prevent unplanned pregnancies that result in high abortion demands.

In both the NGO and private owned facilities, surgical abortion services outnumbered the medication abortion services. Considering the ease of providing medication abortion and the associated minimal complication rates [14,15], one would have rather expected high numbers of medication abortion than surgical options. The increasing numbers of surgical abortions in health facilities calls for further investigations into this observation to further examine what is informing this method of abortion in the study area.

The facility specific contraception and induced abortion figures for January 2010 to December 2017 also reveal that, NGO owned facilities provided higher numbers of contraception and abortion services than the private facilities. In both the NGO and private owned facilities, surgical abortion services also outnumber the medication abortion services. Both facilities provided more short-term family planning services and more surgical abortion services than other services. Studies have shown that where social services are design tailored at the needs of clients’ patronage is high [16,17]. These findings perhaps support those of the current study and call for an evaluation of abortion and family planning providing facilities in Ghana to ensure conformation to national standards and service delivery protocols.

In Accra and Kumasi, the two urban cities of Ghana with multiple ethnicity and religious groupings, efforts being made by the Ministry of Health (MOH), Ghana Health Service (GHS) and its partners on the patronage of contraception and safe abortion services have resulted in a general increase over the years [18]. There has also been a drop in fertility rate from 6.4 percent in the 1970s to 4.4 percent in 2014 [19]. Despite the improvements in family planning, safe abortion services and an increase in available policies and programmes to ensure optimal sexual and reproductive health rights decisions, the expected increase in the uptake of modern contraceptive methods and safe induced abortion services has not been encouraging in Ghana. This is evident by the increase in maternal mortality ratio from 210/100,000 live births in the 1990’s to a projected 560 in 2015 [20], of which unsafe abortions contributes 11.5% in Ghana [21]. There also remain a high unmet need for contraception in Ghana as well as discrepancies between Ghana’s contraception prevalence and fertility rates since the contraception prevalence does not commensurate trends in Total Fertility Rates [19].

Conclusion

The abortion law of Ghana allows abortion on specific conditions and not on demand. The observed increasing numbers of induced abortion statistics in the study area and the reported information of target setting for abortion services in the study facilities however suggest that abortion is being provided on demand and its being used by women carrying unplanned and unintended pregnancies as a family planning method in health facilities within the two urban cities of Ghana. The study therefore recommends a policydirectives for mandatory training and integration of pregnancy options counselling in all health facilities providing abortion services in Ghana. A nationwide strategic assessment of abortion and family planning providing facilities in Ghana is also recommended to ensure conformation to national standards and protocols. The documented increasing uptake of short-term family planning methods compared to the long acting and reversible methods call for more education on long acting and revisable methods, capacity building of providers and availability of commodities to ensure accessibility.

List of abbreviations

ERC: Ethical Review Committee

FP: Family Planning

GDHS: Ghana Demographic and Health Survey

GHS: Ghana Health Service

LARC: Long Acting and Reversible Contraceptive

IDI: In-depth Interview

IUD: Intra Uterine Device

STM: Short Term Methods

LAPM: Long Acting and Permanent Methods

SA: Surgical Abortion

MA: Medication Abortion

SRH: Sexual and Reproductive Health

NGO: Non- Governmental Organization.

Declarations

• Ethical Approval, Consent to participate and for publication

Permission for data collection was obtained from the various facilities used in this study. Written informed consent was also obtained from all participants prior to data collection. To obtain this, participants were informed of the objectives of the study and its intended purpose. The In-depth Interview sessions averagely lasted for 40 minutes. All respondents and facilities contacted during the study agreed and provided verbal consent for the study to publish anonymously.

• Availability of supporting data

The raw data collected is available upon reasonable request

• Authors’ contributions

JAG conceptualized the study and developed the concept note. FYG designed the study, collected data, analyzed the data and developed the draft report. Both authors reviewed the report and finalized it for submission.

• Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to all the facilities and respondents that participated in the study.

References

- United Nations Population Fund 1999. International Conference on Population and Development, (ICPD+5). Conference Report.[Ref.]

- Chiou CF, Trussell J, Reyes E, et al. 2003. Economic analysis of contraceptives for women. Contraception, 68:3-10. [Ref.]

- Åhman E, Shah I. 2007. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. Fourth ed., Geneva: World Health Organization. [Ref.]

- Joshua Amo-Adjei, Eugene KM, Darteh. 2017. unmet/met need for contraception and self-reported abortion in Ghana. "Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare Available online 7 February 2017 Ghana Health Service. 13: 118-124. [Ref.]

- A strategic assessment of comprehensive abortion care in Ghana: Priority setting for reproductive health in the context of health sector reforms in Ghana, Occasional paper. [Ref.]

- Rominski SD, Lori JR. 2014. Abortion care in Ghana: A critical review of the literature Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 59: 550. [Ref.]

- Accra Metropolitan Assembly, Boundary and Administrative Area Archived 2 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. 2009.[Ref.]

- "Demographic Characteristics". 2010. Ghanadistricts.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011.[Ref.]

- Benneh G, Nabila JS, Gyepi-Garbrah B. 1989. Twenty years of population policy in Ghana.[Ref.]

- Belsey EM, Greer HS, Lal S, et al. 1977. Predictive factors in emotional response to abortion: King's termination study-IV. Social Science & Medicine. 11: 71-82.[Ref.]

- Mukkavaara I, Öhrling K, Lindberg I. 2012. Women's experiences after an induced second trimester abortion. Midwifery, 28: 720-725. [Ref.]

- Aniteye P, Brien B, Mayhew S. H. 2016. Stigmatized by association: challenges for abortion service providers in Ghana. BMC health services research. 16: 486. [Ref.]

- Ashok P.W, Kidd A, Flett G, et al. 2002. A randomized comparison of medical abortion and surgical vacuum aspiration at 10-13 weeks gestation. Human reproduction. 17: 92-98. [Ref.]

- Creinin M. D. 2000. Randomized comparison of efficacy, acceptability and cost of medical versus surgical abortion. Contraception, 62: 117-124. [Ref.]

- Choi T Y, Chu R. 2001. Determinants of hotel guests’ satisfaction and repeat patronage in the Hong Kong hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 20: 277-297. [Ref.]

- Augustyn M, Ho S.K. 1998. Service quality and tourism. Journal of Travel Research. 37: 71-75. [Ref.]

- Shapiro D, Gebreselassie T. 2008. Fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa: falling and stalling. African Population Studies. 23: 1. [Ref.]

- Bosomprah, J. 2008. Contextual Issues Affecting the Use of Contraceptives among Women in the Offinso District, Ghana (Doctoral dissertation). [Ref.]

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF Macro. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, 2014). Accra, Ghana: GSS, GHS, and ICF Macro.[Ref.]

- World Health Organization, & UNICEF. 2015. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990-2015: estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. [Ref.]

- Gumanga S. K, Kolbila D.Z, Gandua B.B.N, et al. 2011. Trends in Maternal Mortality in Tamale Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Ghana medical journal. 45:3. [Ref.]